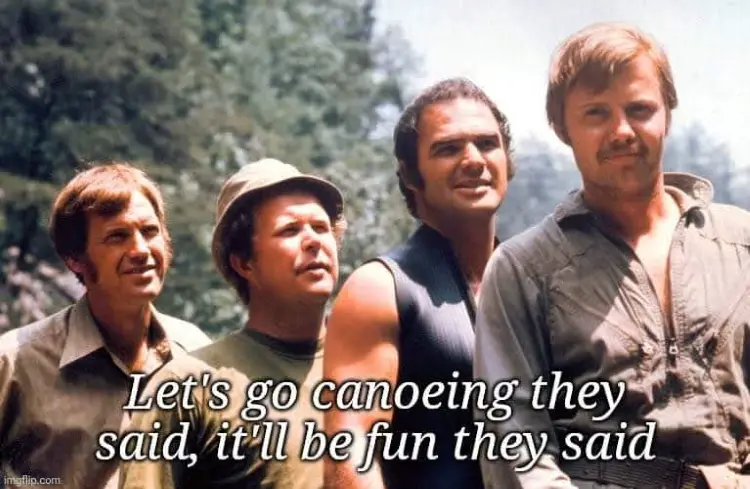

There are many types of bug out vehicles: trucks, dirt bikes, and vans. But if you live near water, what about a bug out canoe?

For centuries, Native Americans used canoes to assist them in their travels. There have been examples found of sturdy yet unwieldy dugout canoes dating back almost 6,000 years in the northeastern United States. Birch bark canoes helped Native Americans and explorers get where they needed to go, reliably and effectively, for many, many years before the technology of plank or strip construction was made available to them.

If you live anywhere near a large body of water – especially large bodies of water with habitable islands or remote areas with no roads, only accessible by water travel – having a bug out canoe should absolutely be on your radar. If you live on the coast (as many people do here in Maine and other locations), a canoe or small personal watercraft can be used to reach remote islands offshore.

Canoes specifically should be looked at for viability and compatibility with your plans, for several reasons that we’ll dig into over the course of this article. However, Bug-out By Boat (or BBB for short) comes replete with several unique challenges that must be considered before you go whole hog on hanging your survival hopes on a small personal watercraft and a couple paddles.

I’ve written a series of articles and done a podcast on other sites describing my past experiences with trial canoe-borne bug outs. Bugging out by boat is definitely a trial-and-error survival opportunity; the more you practice, the more you refine your technique, gear list, skillset, and plans. Here’s what I’ve learned in my canoe adventures over a self-propelled small-craft boating career of 30 years.

The Bug Out Canoe

We’re going to focus on the canoe for this specific article, as it is the most efficient of the human-powered watercraft that should be considered for silently hauling personnel and a significant amount of cargo over an extended distance. Sure – kayaks, rowboats, jon boats, skiffs, and any number of paddled or powered boats can be considered based on your location and the resources at your disposal.

However, the canoe, in my opinion based on my experience, is the most efficient design for your considerations. The canoe provides ample space, comfort, and simplicity for our bug out needs, and is, within craft size limitations, one-man portable and usable. As the ultimate nail in the watercraft consideration coffin, a canoe requires no additional resources to propel: all that is needed is a motivated person and a paddle.

As a definite bonus, canoes and other personal watercraft are relatively inexpensive – for example, if you shop the used market, you can get a top-quality Old Town Canoe, paddles, seats, and PFDs (Personal Flotation Devices) for $1,000 or less. I bought my Old Town Discovery off Craigslist for $450 used, and it came with a set of ash paddles and a home made roof rack system. Once you have a canoe, it doesn’t need to sit unused either! You can use your canoe and enjoy it frequently (while gaining experience) whenever you have open water and some time.

Canoe Considerations

But where to start when considering a BBB? Though there are myriad considerations to make, the first you should probably be looking at is your canoe’s capacity limit. A larger canoe can carry more gear, but will handle poorly when loaded and is a handful to manage in heavier winds – especially if you’re the only one paddling. A smaller canoe will be easier to portage and paddle when fully freighted, but its carrying capacity is accordingly reduced. The canoe itself (and the water you’re traversing) will dictate what you’re bringing along.

Knowing this, it probably will be a good idea when starting from scratch to get your desired gear together and start tallying up the weight. Then look at the number of people the canoe will need to transport, and start doing your research accordingly. If a canoe you’re researching is relatively new and the model number is known, you can head to the manufacturer’s website to find the canoe’s capacity weight.

For example, my canoe is an older Old Town Discovery 158, a polyethylene canoe that is 15’-8” long, and just a hair under 3’-0” wide. According to Old Town’s website, my Discovery 158 weighs 87 lbs. by itself, and sports a total carrying capacity of 1,150 pounds – INCLUDING THE WEIGHT OF THE CANOE ITSELF. Subtracting the weight of the canoe gives us our working gear and person load of 1,063 pounds.

This capacity should be considered the absolute limit to what the canoe can transport on CALM water. Increased weight reduces freeboard – the distance from the water to the lowest point on the canoe’s gunwale – and reduced freeboard means magnified possibility of swamping the canoe and capsizing.

As a personal rule of thumb, I like to reduce total capacity by 10% to improve handling and safety margins. I have had my Old Town Discovery 158 freighted down with about 900lbs of gear and humans, and I can tell you that at this level, my canoe was rather difficult to handle in moderate headwinds with mild waves. In a headwind or strong crosswind, a freighted canoe can be a nightmare to control, especially with only one person paddling.

Weight is your enemy; plan accordingly. Better to leave that heavy gear back on shore and make it to your destination! Rolling a canoe in heavy seas and losing your gear when it’s cold and/or windy is terrifying and incredibly dangerous. It’s no way to perpetuate your safety and survival in a SHTF situation; make multiple trips to move the gear if you have to.

Canoe Construction

Canoes come in five major hull materials: Wood (usually cedar), fiberglass, aluminum, carbon fiber/kevlar, and plastic (polyethylene or Royalex). There are many, many other sources that cover the differences between these materials, so I’ll just breeze over the basic material attributes so you can start your search in the right direction.

Wood

Wood is a lovely material for a traditional canoe; sometimes covered in a coated canvas, wood canoes are graceful and gorgeous. Many people (including myself) dream of someday building a cedar strip canoe in their garage and paddling serenely out on calm water to cast a fly over a rising mayfly hatch. However, for a bugout canoe material, wood should probably be overlooked unless you need to have an initial source of firewood when you get where you’re going.

The complex, sweeping, graceful curves of a wood canoe are divine to behold, but a nightmare to repair in the field. Wood canoes are also very heavy and very expensive due to the large labor cost of building; regular maintenance is also required. Best keep looking at other materials unless a wood canoe is all you’ve got.

Fiberglass

Fiberglass canoes have been a staple of the outdoorsman for decades. I remember paddling a 16 foot fiberglass Mohawk canoe all over the many waterways of Maine while growing up, and I have many fond memories of that beastly old canoe. What I don’t recall fondly, though, are the utter weight of the fiberglass canoe, and its propensity to crack and bust apart under even minor rock or log impacts.

Show me a fiberglass canoe that’s seen any kind of moderate use, and I’ll show you a canoe with myriad fiberglass patches along the bow, keel, and hull. However, if you have the materials (fiberglass matt and epoxy) you can keep a fiberglass canoe patched up and running for a long, LONG time. My Dad still has that 16’ Mohawk, and it’s still ready to go even though patched heavily.

A nice big fiberglass unit will be easy to find online for not much money, be easily repairable, rigid and efficient in the water though kinda heavy out of the water. Fiberglass isn’t my first choice for a bugout canoe, but I’d never turn my nose up at a good one.

Aluminum

Aluminum canoes were made for years as a mass produced workhorse watercraft system. The mass production and metalforming efforts learned in WW2 in aircraft production led companies like Grumman to engage these efforts in other forms of transportation – like canoes.

While aluminum canoes are sturdy as hell due to their all metal construction, they tend to be extremely heavy, loud (anyone who has been in an aluminum canoe remembers the “SMACK” an incoming wave makes hitting the side of the hull), and comparatively inefficient in the water – though still very capable.

If you have another person to help you lug a 75-100 lb canoe along, aluminum canoes can work great – but if the hull stresses and cracks or breaks, the only permanent repair you can affix is welding; be sure to pack JB Weld in your emergency aluminum canoe gear for semi-permanent fixes.

Carbon Fiber/Kevlar

Newer to the personal watercraft scene, carbon fiber and kevlar canoes are immensely strong and incredibly lightweight. However, there’s no free cake, and the price you pay for these lightweight wonders is literal; kevlar and carbon fiber canoes are quite (okay, very!) expensive. These synthetic fiber canoes are wonders, but you’d best get out your wallet if you’d like to have one available for your bugout.

Repairs in the field are more difficult as well; I’ve never effected a repair on one of these types of water craft, but the process is similar (though more elbow grease is required) to fiberglass canoes. But if you’re a one-person show and you need to manage your canoe and portaging by yourself, the lightweight synthetic fiber canoes are probably the best bet. The light structural weight of the canoe itself also means that less of the hull weight goes towards the canoe’s total weight capacity.

Plastic

Plastic (polyethylene and Royalite) canoes, along with aluminum canoes, are the real workhorses of the canoe lineage – inexpensive, tough, and accessible, a good quality plastic canoe will do everything you can ask of it and keep coming back for more. My $450 Old Town Discovery 158 has traversed many New England lakes and rivers including the Allagash Wilderness Waterway, and I couldn’t ask for a better canoe.

While they can be a bit on the heavier side, plastic canoes can be dragged down rocks, skidded over submerged logs, flipped, banged, and impacted with wild abandon and little concern for damage to the canoe itself. There is zero maintenance required and, as far as I can tell, no need for repair gear. Available for reasonable amounts of money in any size and configuration you can dream of, a plastic canoe would be my first recommendation for anyone looking for a bug out canoe to haul their gear through the apocalypse.

Hull Design

I won’t get too deep (pun intended) into this subject, since for many of us the canoe hull design is a byproduct of buying the appropriately sized canoe in our price range; you may just have to live with what you get.

However, there are a few things to note: wider canoes are more stable (a good thing), while also providing more surface area to have to push through the water, increasting paddling fatigue (a bad thing). Generally speaking, I like wider canoes for their stability and accept the fact that they will be slower in the water.

Another design attribute to note about canoes is that they can have a keel (usually referred to as “lake canoes”) or not have a keel (“river canoes”). A keel in a canoe is a long longitudinal ridge that runs the length of the canoe along the bottom center. Usually only an inch or two tall, a keel is a small feature that does a big thing.

Keel-equipped canoes are more stable and generally track much straighter in open water than non-keel equipped canoes. This means that you can travel in a straighter line across long stretches of flat water; this adds up to less time to get to your destination and less frustration keeping the canoe on course. It also can help keep the canoe tracking where you want to go in a head or side wind.

Canoes without keels are far better suited for fast moving river water or rapids, where they have more clearance under the boat to ensure you don’t catch on rocks or logs. Of course, they are usable on lakes and large expanses of water – just know you’ll generally be fighting the canoe to go where you want, meandering left and right along a course instead of tracking straight.

The other hull design decision is square stern vs. traditional hull shape, which is pointed at both ends. A square stern canoe is flat at the back, and designed to mount a small outboard or trolling motor to propel the canoe across the water. However, if you’re not using a motor on your square stern canoe, they are markedly more difficult to paddle through the water through decreased hydrodynamic efficiency.

If your bugout plan can accommodate the added weight, flammable gasoline, and noise of an outboard, a square stern may be a viable option for you. However, if your bug out canoe is going to be human-powered only, do yourself a favor and shop around for a traditional canoe hull shape.

Canoe Gear

Speaking of gear, we need to chat a few things over, friends. When you’re in a canoe, you’re literally surrounded by moisture. That moisture will absolutely be getting on your prized possessions whether you like it or not. Even if you don’t roll or capsize your trusty canoe or kayak, you need to remember that spray, rain, and water dripping from your paddles will permeate all the things and build up in the bottom of the canoe. Know this going in, embrace the facts and prepare up front to insulate your gear from water. You’ll be a lot happier overall.

Dry Bags

The first items you should be looking at are dry bags. Dry bags are heavy-duty, thick-walled rubberized bags with no zippers (zippers leak!) and an open top with reinforced edges that fold and roll over, then tie or clip together to create a sealed container. Provided they stay unpunctured, dry bags are a stellar way to keep your gear dry – and if sealed properly they even float! Dry bags are available in myriad sizes and colors.

Pay a few extra bucks for better quality dry bags, it’s worth the investment. Some even come with backpack straps for excursions away from the canoe. Plan on putting all high-value gear on a dry bag – electronics, warm clothes, fire starting gear. Just be sure to watch items with sharp/square edges as they can puncture the sides of a dry bag under some conditions.

Zip-Lock Bags

Zip-Lock Bags for protecting small electronics and other must-stay-dry items like books, wallets, or important documents, high quality resealable bags are outstanding. I will usually double up bags on really important items and keep both bags relatively full of air – if they go overboard, the bags will keep your items afloat if properly sealed. Don’t cheap out – spend the extra buck a package on heavier-duty resealable freezer bags; they will be reusable for a long time.

Tarps

Tarps especially tarps with grommets – are a Godsend when canoeing as well. You can run a tarp over the inside or the outside of the canoe, and secure with bungee cords, rope, or paracord. You can even wrap your gear up like a big plastic-covered burrito and keep it mostly dry. The tarp can double as a shelter once you’re feet dry as well. While tarps can never fully seal your gear against water like a dry bag can, they’re an excellent multi-purpose first line of defense against the elements.

Canvas

A bit of a dark horse in the canoe gear additions, canvas really appeals to me personally as a bit of a historical nerd. Years ago I saw pictures of old wilderness men traversing the back country waterways in their trusty cedar strip canoes, with fitted waxed or greased canvas coverings over the precious contents of the canoe. Before the heyday of plastics and the invention of dry bags and tarps, waxed canvas or leather skins kept the gear dry for generations.

Still every bit as functional as a tarp but a bit less impervious to weather, canvas coverings are still effective and functional. If you’re good with a sewing machine and scissors and aren’t afraid to drill some holes in the gunwales of a canoe, you can fashion a canvas cover that uses stainless steel snaps to cover the cargo areas of your canoe. In a pinch, you could use the canvas as an effective shelter or even rig a sail if you felt so inclined.

Repair Gear

Your canoe can get holes, despite your best intentions and actions to maintain its watertight integrity. Having the ability to patch small holes in situ well enough to get you to your next location is key. Fiberglass matt and epoxy is a pretty good bet, as are two-part epoxies like JB Weld. Just remember – if your canoe flexes while in use (I’m looking at you, plastic canoes), chances are the repair will eventually pull away from the canoe hull. Repair the inside and outside of the hull for a little redundancy insurance.

Paddles

As the old proverb goes, you never want to be up a SHTF creek without a paddle (or something like that.) Paddles are the main method of locomotion for canoes and kayaks. Not clumsy or loud like an outboard motor, paddles are an elegant propulsion method, for a more civilized age.

Like the canoe itself, there are many profiles and materials for paddle design. The most important rule for paddles on a canoe is: HAVE A PADDLE. And a spare or two! Canoeing is fraught with moisture – rain, the water you’re floating in, sweat. Paddle grip surfaces need to be smooth for easy transitioning from side to side, so positive gripping surfaces are not terribly prevalent on a canoe paddle.

This leads to dropped paddles – it happens to everyone. If you lose your only paddle when you’re in the middle of a lake, you’re shafted. Having a spare paddle – I like small collapsable paddles for emergency backups – will be godsend if your main paddle decides to literally jump ship.

As I said, there are many shapes of paddles – generally speaking, go with a nice wide ottertail or beavertail shape – these really grab the H2O and provide a good push for moving the canoe through the water. But be sure to purchase sturdy, strong paddles – the material doesn’t matter a whole lot in my book.

Ash or similar wood paddles are traditional and good at what they do, and can be repaired or refurbished with epoxy and polyurethane as needed. Plastic and aluminum paddles work as well, but the cheaper ones can bend or break with little abuse. Just be sure to spend a few bucks on some good paddles, and make sure they are light to reduce paddling fatigue.

Paddles will be used to not just drag a canoe through open water, but will be used as push bars to keep your canoe away from rocks and obstacles, pry cars to move the canoe through shallow water, and dug into the bottom to keep your canoe on station. These are tools that will see abuse, buy the best ones you can. I really like L.L Bean Beavertail Canoe paddles; they are beautiful and tough – but for long-term use, plastic, aluminum, or kevlar paddles may be a better choice.

The length of canoe paddles is a discussion all unto itself, but I try to keep canoe paddles to around 4-5 feet long, with a longer paddle provided to the person up front. With the longer paddle, they bow crew are able to reach out and push the bow of the canoe away from snags and obstacles, plus be able to drive the paddle deep for lots of bite when in open water. This propels the canoe forward while the person in the stern assists with paddling while steering the craft.

Personal Flotation Devices (PFDs/Life vest)

PFDs, though listed last here, should be the very first canoe accessory you buy, whether you are planning its use as a bug-out vehicle or not. A PFD is the seat belt of the canoe: it keeps you alive and floating in the correct orientation in case of a crash or capsizing. Most areas absolutely require one PFD per person on the watercraft, but many laws do not require the user to be physically wearing it.

Whatever the bylaws, personal flotation devices need to be considered an utter necessity for your canoe. They can range from the inexpensive bright orange, blocky, styrofoam-filled life vests to the pricey, form-fitted units that offer pockets, ventilation, and quick on/off. Whatever you get, be sure it’s fitted to you properly and that the vest is USCG approved.

If you have a little one to plan for, be sure to find a children’s life vest, and be sure to keep the vest size updated as they grow. I like Stearns vests as a good value between quality and price, but there are literally thousands of options for you. Be sure to try your vest on and run through a cycle of arm and waist motions before you buy; an ill-fitting life vest just plain sucks. It will chafe, bind, and if too big, can try to slip off your body in the unlikely event of a water landing.

Additional Accessories

While the above should be considered essential items for a bug-out canoe, definitely consider the following to make your life easier. These should be considered as addition to your normal survival gear like fire starting apparatus, water filtration, knife, etc.

Flip-up Canoe Seats

Canoes, of course, come standard with seats for its passengers; they can be wood, molded plastic, or aluminum. The stock seats are certainly functional and will work in a pinch, but certainly look into upgrading your piercing situation.

I have a terrible back after years of thrashing my body with wild abandon in my younger years as a construction worker, so after 20 minutes or so, my lumbar is absolutely on fire after sitting on a canoe seat. I frequently say that the best $40 I ever spent was for the GCI Outdoor SitBacker strap-on folding canoe seat. These lovely items simply attach to the existing canoe seals with sturdy nylon straps and polymer buckles. Once properly adjusted, the fold-up set backs offer outstanding back support, allowing you to lean back and get comfortable while serenely paddling your personal watercraft. If you have a few bucks and you’re planning on using the canoe frequently over long distances, do yourself a favor and get them. You can thank me later.

GCI Outdoor SitBacker Adjustable Canoe Seat with Back Support

- Supports 250 lb (113.6 kg);Open size: 12.2 x 16.5 x 17.9 in (31 x 42 x 45.5 cm);Seat width: 16.5 in (42 cm);Folded size: 3.7 x 16.3 x 16.5 in (9.5 x 41.5 x 42 cm);Unit weight: 2.9 lb (1.3 kg);Seat strap length: 17 in (43.2 cm)

- Canoe Seat: Made using only the highest quality materials, our field-tested canoe seats with back support are exceptionally easy to open, close, and carry

Nylon Line (rope)

Lines, while not essential, should really be considered as preferred gear to have on your canoe. Paracord can work in a pinch, but remember that a large enough canoe can easily weigh over 750 lbs fully loaded so it can’t hurt to have some beefier lines available. Be sure to choose material that is UV resistant, impervious to water, and easy on the hands.

I usually try to bring 50-100 feet of nylon rope with me to be able to lash the canoe to trees on land to keep the canoe in place while unloading, to drag the canoe through really shallow water while you walk in the river or on land, or to run an anchor. I don’t like using chains, as they are rather inflexible in use, can rust, are very heavy, and make lots of noise.

Anchor

An anchor in a canoe is used to keep the craft in one place in the water. Usually used for fishing, they can be used to keep a canoe still and silent, or in a lovely cove in the sunshine for a bit of paddling respite. However, they can add quite a bit of weight to the canoe’s payload for limited use, so be sure you need one before you add it to your boat’s cargo manifest. I usually like mushroom-type anchors of about 15-20 lbs weight for canoes in the 14 foot to 16 foot length. Use carabiners at the end of a rope to quickly detach the anchor and use the rope for other purposes.

Maps

A good waterproof map set can be a Godsend if your bugout plan is less than pre-planned. A map set worth its salt will show fast water and/or rapids, terrain, portage locations, campsites, and other essential information. I like Delorme’s Atlas & Gazetteer books; they are heavy-duty, available for every state, and the detail and information they provide is worth every penny.

Footwear

While canoeing, you’re going to be getting your feet wet. Just accept the fact and roll with it. If the weather isn’t brutally cold and/or if I have a fire available in short order, I’ll usually wear lightweight footwear that drains well and dries quickly. Crocs, water shoes, and my favorite, low-top Converse All Star sneakers, work really well as canoeing footwear as they offer drainage and will be dry before you know it. Flip-flips and sandals don’t work that great as sometimes when disembarking your foot will go a long ways down into muck. Frequently, your sandal won’t come back out with your foot.

For colder weather/water, a lightweight, tall rubber boot will keep your feet dry under most circumstances – but they can be tough to get off your feet if you go overboard and prove to be heavy.

Exposure Protection

Okay, so your gear is wrapped up in zip lock bags and dry bags, but what about you? Be sure to have lightweight rain gear available to fend off unexpected precipitation that falls before you can get to shore. Also, a good baseball cap or brimmed hat can be a godsend to keep the sun off your skin – remember, if open water there is zero shade and the water can reflect sunlight back UP, exposing your skin to UV rays in areas you didn’t think could get sunburned. Sunblock is essential, as is bug spray and/or a bug net. Keep these items in the top of your dry bag for ready access.

Small Bucket

Water gets in canoes, whether it be from rain, paddles dripping, or leaks. A small bucket or cup can help bail out the extra water before it builds up and drenches you and/or your gear.

Tips and Tricks for Canoeing

Canoeing is largely a skill that is obtained by getting out there and DOING IT – it’s not something you can suddenly do well just by having the canoe, some paddles, and an idea of the procedure. So tip number one: put on a PFD and go try it out! Three hours on the water under non-emergency controlled situations will teach you more than a thousand hours of watching YouTube videos. The more you do it, the better you get – and that’s a fact.

That being said, here are a few basic tips I’ve learned along the way I’d like to share to help you along on your BBB journey.

- Have an extra paddle, and lash it to the canoe. Paddles, despite the best of intentions, can float away from the canoe. Have an extra, and tie it to a seat or cross brace with a carabiner or easily disassembled knot. That way, in case of a flip-over and you lose everything, you can right the canoe and paddle to shore.

- Flip your canoe. That’s right, go out on some calm water not far from shore, just deep enough so your feet don’t touch, and roll that sucker over. Learn how to right a canoe when it’s been rolled and you’re floating in the water next to it.

A canoe usually won’t sink when rolled; some practice will show you how to get the canoe back in its proper orientation and how to get yourself back into the canoe. It’s a process but doable – and not something I would recommend trying to learn on an actual bugout when the chips are down and it’s 45 degrees outside.

- Keep fire-making gear and a knife in a sealed waterproof bag on your person! Years ago, my brother, father, and I were out bass fishing and rolled the canoe when my brother stood up while trying to retrieve a lure that had been stuck in a tree via bad cast.

We weren’t far from shore so we were able to trudge back to shore and drag the canoe with us, but it was late April in Maine and it got cold FAST. Fortunately, I had a lighter in a zip lock bag in my pocket and we were able to get a roaring fire going in no time to dry us out before hypothermia became an issue.

- If you have a small motor on your canoe, don’t be afraid to ditch it on shore and go out and propel yourself by paddle. Canoes just really kinda suck to use with an outboard or trolling motor; they’ve evolved over centuries to be highly efficient at coursing through the water via paddle propulsion. Outboards really just add weight and make the canoe unwieldy – even more so if you’re using an outrigger setup for the motor.

- Learn how to read the weather. When you’re on the water – especially big water – winds and rain can kick up FAST, endangering your watercraft fun time. However, the weather usually has tells that it will be ramping up. Lean how to read these tells and you won’t be caught in the middle of a big lake with two foot waves and a canoe freighted with gear.

- When that weather does kick up, stay close to shore if you need to keep moving! If you roll the canoe due to a rogue wave, you will hopefully be in shallow enough water that you can stand up and easily recover any dumped gear. Ideally your vital gear will be in dry bags that stay floating.

- Carry some dry firewood and kindling with you, even if it’s just a couple pieces. Plug it into a dry bag or wrap it really well so that you have nice, easy-to-light wood in case of an unplanned shore stop. This wood can save your life or at the very least help dry some clothes and dry out any locally sourced firewood.

- Learn how to load a canoe. All the heavy stuff should stay low and centered inside the canoe. Pack the lightweight gear around the heavy, centered gear periphery. Items that need to be souced while you’re in the canoe should be on top and easily accesible without having to stretch yourself a long ways or reach around behind yourself.

These awkward reaches can quickly make you lose your balance, and in the drink you go! Also, if you have anybody sitting in the bottom of the canoe – especially children! – make sure they know that they need to stay in the center of the canoe and not to suddenly lean over to shift or peer overboard. If they’re not careful, they might just get a really up close and personal (and much wetter) view of whatever they wanted to see!

- If you’re canoeing with another person, learn how to work as a team! Not much is more frustrating to a seasoned canoe runner to work with someone who’s never paddled a canoe. Usually, the person in the back (stern) steers the craft and provides additional paddling power, while the person sitting in the front (bow) picks a side to paddle on and keeps at it on that one side until they need to switch to to fatigue.

When I take canoe newbs out and plunk them in the bow, invariably they’ll switch paddling sides frequently and try to help steering where they think the canoe should go! This can be maddening to the guy in the stern, as usually they are already in the process of guiding the craft where they need to go, and the two people are counteracting each other. Communicate on a system and stick with it to minimize extra work and frustration.

- If you’re in a canoe solo and find yourself in a crosswind, you better hope you have some weight packed way up fron in the bow of the canoe. You may have seen people canoeing by themselves with no other weight, bow carrying high out of the water, slapping on the waves.

In a wind, that high bow is a beautiful sail, and you’ll find it will catch and whip that canoe right around (or over!) – and you’ll be powerless to do anything but what the wind wants. Either get on shore and wait for the wind to die down, or get some weight up front to (hopefully) help out a bit.

Wrapping it Up

Canoeing is a soothing, lovely form of recreation on the water, and one of my favorite ways to spend my time. While my personal bugout plans don’t involve canoeing anywhere, I do enjoy having the gear and ability to use a canoe to get my family and emergency gear out to even more locations if needed. An old canoe is a great item to leave at a bugout location!

You can get started with a good sized canoe and all the safety gear and paddles you need for $500 or under if you shop used (Craigslist and yard sales are great first stops) and you’re not picky about the canoe appearance.

Even better, many camps or outdoor recreation areas will have businesses that will rent you a canoe; this is a stellar way to get your feet wet (pardon the pun) in the canoe world. Even better, find someone who has a canoe who can take you out and teach you a thing or three about moving a canoe through the water safely.

If worse comes to worst, an experienced person with a canoe and a place to go over the water has an efficient way of moving people and gear silently when a bugout by boat is on the menu. If the worst never comes, I can guarantee you that same canoe and experience will bring you and your family many, many hours of fond memories and smiles. It’s a win-win and absolutely worth your consideration.