Just last week a dead NASA satellite crashed back to Earth amid warnings it had a one in 2,500 chance of killing someone.

As it was, the spacecraft smashed harmlessly into the Sahara Desert somewhere between Sudan and Egypt, but it once again highlighted the increasing risk of space junk in our daily lives.

Such is the scale of the problem that scientists have even warned there is a 10 per cent chance that a person could be struck and killed by a falling spacecraft or spent rocket booster within the next decade.

The European Space Agency estimates that there is more than 10,800 tons of space junk currently orbiting the Earth, including 130 million objects that include a nine-ton Russian rocket, Cold War spy satellites and the 12-ton iconic Hubble.

Here, MailOnline takes a look at the biggest debris up there, and when we need to watch out for it.

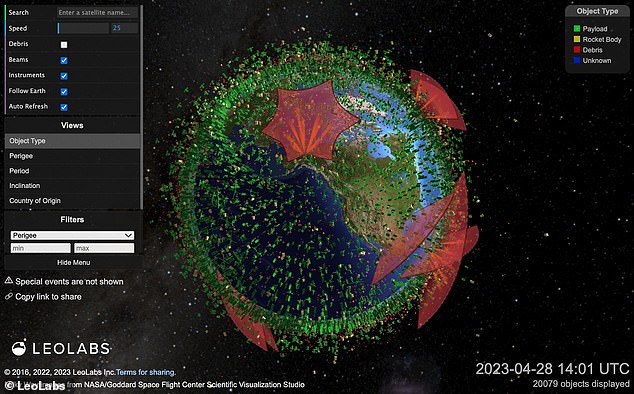

Concern: MailOnline takes a look at the biggest debris up there, and when we need to watch out for it. This still image, from the satellite monitoring and collision detection firm LeoLabs, shows the space junk that is currently circling the Earth

Russian rockets (9 tons EACH)

Some of the biggest objects of concern are spent Russian rocket boosters launched between 1992 and 2001.

They include 18 examples of the nine-ton, 36ft (11m)-long upper stage of a Russian Zenit rocket, which are currently lurking in what has been termed a ‘bad neighbourhood’ around 520 miles (840km) high.

‘They’re like a big yellow school bus without a driver, without brakes,’ said Darren McKnight, a senior technical fellow at satellite monitoring and collision detection firm LeoLabs.

Some of the biggest objects of concern are spent Russian rocket boosters launched between 1992 and 2001. They include 18 examples of the 9-tonne, 36ft (11m)-long upper stage of a Russian Zenit rocket (pictured)

The Russian rockets are currently lurking in what has been termed a ‘bad neighbourhood’ around 520 miles (840km) high

The good news is that at this altitude it will take centuries for the debris to crash back to Earth.

But it’s still coming down eventually, unless we can find a way to safely remove it — which is why there is an increasing number of startup ventures trying to come up with concepts for how to do this.

China’s Long March (23 tons)

There has been a lot of controversy over China’s Long March 5B rockets, which are of great concern due to their size.

Just last year, there were warnings that debris from one out-of-control Long March booster could come down over a populated area.

Fortunately it crashed to Earth over the Indian and Pacific oceans, but this rocket will not be the last of its kind that causes alarm.

Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told MailOnline the Long March 5B boosters were among ‘the most worrying’ because they are so large.

The problem with China’s rockets is rooted in the risky design of the country’s launch process.

Usually, discarded rocket stages re-enter the atmosphere soon after lift off, normally over water, and don’t go into orbit. But the Long March 5B rocket does.

There have been calls by Nasa for the Chinese space agency to design rockets to disintegrate into smaller pieces upon re-entry, as is the international norm.

But Beijing has previously rejected accusations of irresponsibility, with the Chinese Foreign Ministry saying the likelihood of damage to anything or anyone on the ground is ‘extremely low’.

There has been a lot of controversy over China’s Long March 5B rockets (pictured), which are of great concern due to their size

Hubble Telescope (12 tons)

Another object that is enormous.

Although Hubble is still going – and likely able to extend its 23-year stay in space by another decade – when its mission does finally come to an end it could become a problematic piece of debris.

NASA has said it plans to ‘safely de-orbit or dispose of Hubble’ at the end of the telescope’s lifetime, but this may be easier said than done.

Although the iconic Hubble Telescope (pictured) is still going – and likely able to extend its 23-year stay in space by another decade – when its mission does finally come to an end it could become a problematic piece of debris

Unlike some of the modern Starlink satellites being launched into constellations above Earth, Hubble has no onboard propulsion system that could slowly lower its altitude and bring it safely down in the ocean.

Weighing a whopping 12 tons, that has the alarm bells ringing.

This is also not a problem scientists have decades to solve, either. Because Hubble is in a relatively low orbit about 332 miles (535 km) above the Earth’s surface, it would likely take only a few years to crash back down.

Unlike some pieces of debris, experts can’t rely on it fully burning up in the atmosphere during re-entry either.

That’s because its huge size means large chunks of it could well wreak havoc by damaging aircraft in the air or hitting humans and buildings on the ground.

Envisat (8 tons)

This European Earth-observing satellite is another that has earned its place among the potentially deadly space junk items because of its sheer size.

Weighing around eight tons, Envisat is one of the largest pieces of space junk in orbit.

The satellite has been dead since shutting down unexpectedly in 2012, when it did not respond to any commands.

Weighing around eight tons, Europe’s Envisat is one of the largest pieces of space junk in orbit

It was a bitter blow for the European Space Agency (ESA) in more ways the one, in part because it was seen as Europe’s flagship Earth-observing satellite and secondly due to it being a blot on the reputation of an agency that prides itself on sustainability.

Envisat was launched in 2002 as the biggest non-military Earth-observation spacecraft ever put in orbit. It went five years beyond its planned lifetime but shut down two years earlier than ESA had hoped.

Cold War spy satellites (1 ton each)

Another Russian rocket, this time the SL-8, delivered about 145 Cold War spy and communication satellites to space between the 1960s and 1990s.

The satellites are no longer in use but they are clogging up near-Earth orbit, with each of them having a mass of 1,760 pounds (800km).

Both they and the spent SL-8 rocket stages are problematic because they cannot be controlled and could fall back to Earth at any time.

When they do, recent research suggests that those living in the global south will be at highest risk, with errant parts three times more likely to land at the latitudes of Jakarta, Dhaka and Lagos than those of New York, Beijing or Moscow.

The study was carried out by experts at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Another Russian rocket, this time the SL-8, delivered about 145 Cold War spy and communication satellites to space between the 1960s and 1990s

The International Space Station (400 tons)

Much like Hubble, the International Space Station will eventually have to be retired.

NASA is currently planning to do this by 2031, but the process will take several years as the observatory’s orbit is gradually reduced by visiting spacecraft.

The US space agency can do this with a bit more control than Hubble, however, so although the ISS weighs almost 400 tons, it can be brought down somewhere in the South Pacific Ocean Uninhabited Area.

Much like Hubble, the International Space Station (pictured) will eventually have to be retired

A lot of the space station will burn up on re-entry but there will still be a large amount of debris expected and it could make quite the spectacle for anyone looking up at the night sky within its relative vicinity.

It should crash back down to Earth in January 2031.

The ISS itself is no stranger to space junk. It has actually had to carry out 29 debris avoidance manoeuvres since 1999, including three in 2020 alone.

What doesn’t help is that some countries have decided to deliberately blow up their satellites with missiles as part of military test manoeuvres.