I came into the mountains last June at the so-?called golden hour, through cliffs the color of sand and grace. Wildfire smoke made the whole Western Slope seem becalmed, as if through the particles the sun breathed soft light. Time layered in stone, olive, rust, and dusky violet. I was listening to Christian radio. A preacher from Wisconsin. An amiable voice, beneath its surface a sense of fracture. Ochre, if I had to give the preacher’s voice a color.

“Quite a few years ago,” the preacher mused, “we went to the coast. I was studying on the beach while my three teenage boys were out in the ocean.” His three boys frolicked in the waves; the preacher considered God’s word. Sound sifted away—?until the preacher heard his wife screaming. “She said, ‘Honey.’?” He had shorn the memory of alarm. “‘Do you hear the boys hollering for help?’” In his telling she asks as if she is simply curious. Do you hear our children drowning? “I looked up. And listened. I said, ‘Well, it kind of seems like they are.’?” He dropped his Bible in the sand, he sprinted to the water. “Only problem, I was wearing blue jeans. Have you ever tried to swim in blue jeans?” His legs were heavy. The water carried his boys away. “The undercurrent,” said the preacher. The undertow. “I was drowning myself,” he observed.

And then—?I don’t know. The radio signal stayed strong, the preacher kept talking, his voice carrying me up into darker canyons too steep for the setting sun. Evidently, he survived. His three boys? He never did mention. The story, which we may imagine as beginning in fact, had been made into parable, the meaning of real things smoothed like sea glass. Myth carries people away. The preacher spoke more about the weight of his jeans. “The weight of our lives.” The weight, he said, is anything that distracts us from God. His sovereignty. His authority. That was all that mattered, even more than his three boys. The “weight” that drags you down could be anything. “It may be a love.” Even for your children. “Lay it aside,” he rumbled. There is no saving this world.

When I first came west at nineteen, I had my own religion. I thought that the mountains were the Earth’s secrets rising to be seen, by me, as if geology were revelation. This is a widespread misperception. Over the years, I came to think of them instead as indifferent, not made for me or anybody, not made at all. There is no intention.

But now, driving, I saw them as tender. Maybe it was the haze. These mountains still grow but as they do their peaks soften and drift down to the plains. They rise, they subside. I thought of Andrew, my friend, who would be soon riding his bicycle up this spine across which I drove. His mind would be clear. “I don’t really do the past.” Neither do the mountains. I imagined them sleeping. But they were never awake. Or always awake, always sleeping, rising, sinking. How does a body come apart? How does democracy dissolve? It subsides.

I drove down a riverine valley into the town of Rifle. Riparian green punctured by factories and grain elevators, the spike of a steeple at the edge of town. Shredded tire on the road and two men by a broken blue pickup, hood raised, drinking beer and watching the sun’s last smoke-?filtered light, purple and violent, shot through with the palest of pink hues. Dead deer down by the water, its body half-?open.

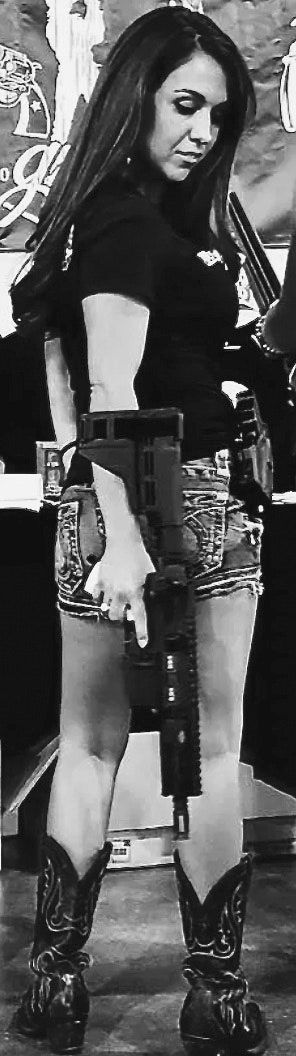

I was hoping to eat dinner at a restaurant I’d heard about called Shooters. Like Hooters, but with guns. Waitresses in cutoffs, each of them armed. It was the creation of a congresswoman named Lauren Boebert, and she carried too. “I am the militia,” she’d declared. There’s a photograph of her flanked by two servers in their Daisy Dukes and cowboy boots, armed with eight guns between the three of them. Boebert looks back over her shoulder, not at the viewer, but down at the assault rifle the buttstock of which she is framing—?no other way to put this, one must respect self-?presentation—?with her ass.

“Buttstock,” though, is only the correct term if it’s a rifle. This gun may actually be a very elaborate pistol. “For an AR-?15 to be that short and still have a buttstock,” a gun enthusiast friend told me, “it would need to be registered with ATF as a ‘short-?barrel rifle’”—subject to much greater regulation. “The ‘pistol brace’ she has in place of a stock is meant to be clamped around your forearm to stabilize the weapon if you fire it like a pistol.” My friend called it a “photo-?op gun”—?lacking a sight, he said, “you could point it at something and maybe hit it, but definitely couldn’t hit anything at a distance that would require adjusting aim for vertical drop or wind.”