James Carville stretched out his legs and leaned far back in his chair behind a rooftop table at the Peninsula Hotel in Beverly Hills. The Peninsula is a gathering spot for Hollywood celebrities and executives but Mr. Carville, who is neither, was the object of attention on this afternoon.

“It’s the economy — nice to meet you, Mr. Carville!” a lunchtime patron said as he passed by the table, recalling (if incompletely) the campaign slogan that Mr. Carville championed as the chief strategist for Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign.

A few moments later, as Mr. Carville recounted for a reporter his efforts to convince Democrats that an aging President Biden would lose to Donald J. Trump if he stayed in the race, Jenny Durkan, the former mayor of Seattle, walked over and declared: “You were right!”

“Thank you, darling,” Mr. Carville responded in his native, languorous Louisiana accent.

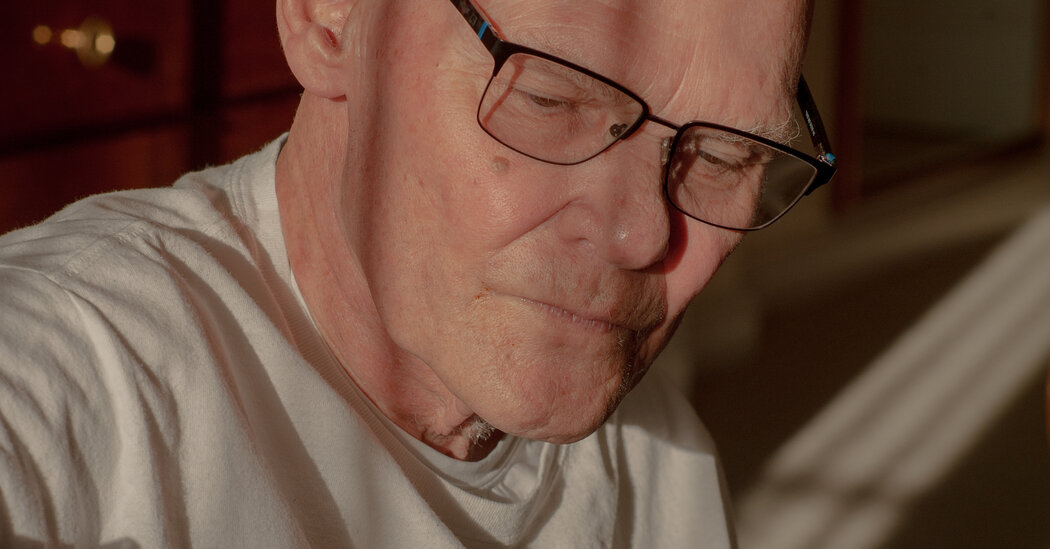

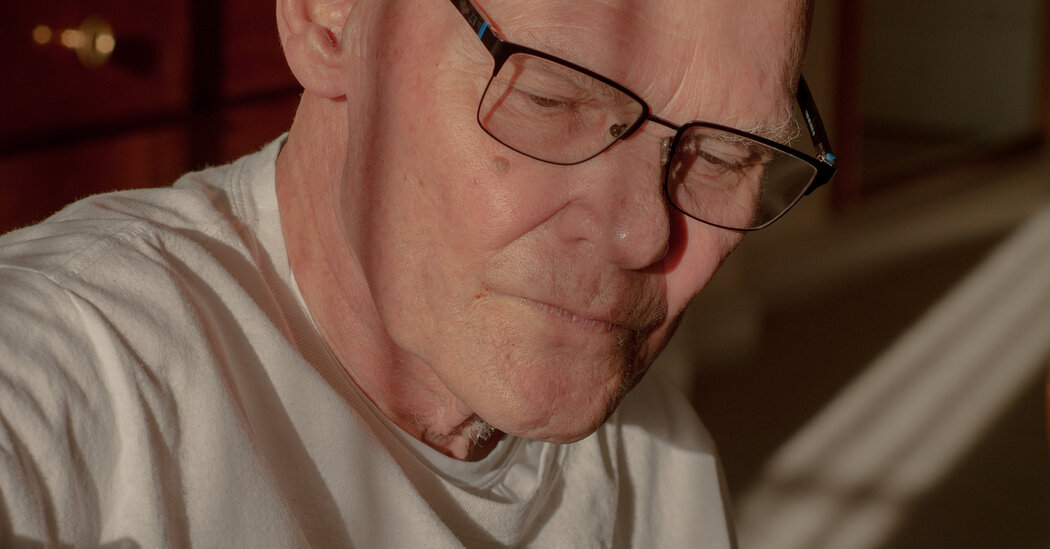

It has been 32 years since the campaign that put Mr. Clinton in the White House and, in the process, established Mr. Carville as a celebrity in his own right. And now, at the age of 79 — he is turning 80 later this month — Mr. Carville may well be as prominent as ever. He says the contest between Vice President Kamala Harris and Mr. Trump is the last he will play a role in, and it has given him what would seem to be a last hurrah.

In a matter of weeks this summer, Mr. Carville went from being a lonely figure in his party, warning about the perils of keeping Mr. Biden on the ticket, to cheering from the sidelines as Mr. Biden ceded to pressure from leading Democrats to stand down.

“He was one of the first inside the Democratic Party to speak out openly and say this will be a mistake: that the American people do not want these two men,” said Karl Rove, the longtime Republican consultant. “That took a lot of courage.”

Mr. Carville is well aware that he might shoulder some of the blame should Ms. Harris lose, an outcome he says he doesn’t think is likely. But he does worry. In recent days, he said, he has been concerned that she was running too passive a campaign.

“It strikes me that they are really good at big events,” he said. “I don’t know how good they are at trench warfare, at the day-to-day news cycle. They haven’t done anything wrong. But they haven’t really done a lot in the past couple of weeks.”

If she does lose, he said, “it will be quite a mess.”

Whether Ms. Harris wins or loses, Mr. Carville’s role in the upheaval has elevated him to a level of prominence he has not had for years. He is a regular on television news talk shows and hosts a podcast. He is writing opinion essays. And he is the subject of a documentary that will be released in theaters across the country: “Carville: Winning Is Everything, Stupid,” by the filmmaker Matt Tyrnauer. (Mr. Tyrnauer said he sped up finishing his documentary to capture Mr. Carville’s efforts to push Mr. Biden out).

“There is a very small club of people who can maintain a 30-year arc of continuous fame and not have it be consumed by scandal, or take a dip — and James is definitely in that club,” Mr. Tyrnauer said.

It is a fitting turn of events for Mr. Carville who, after the Clinton campaign — and after he was a central figure in the 1993 documentary “The War Room” about that race — decided that he was too much of a celebrity to be a behind-the-scenes operative in an American political campaign.

“Once you become a famous person in the United States, it’s not a bad life, but the only thing you can do is just be famous,” he said.

“I’d love to come back and be a campaign manager for a day because I just loved it,” Mr. Carville said. “But I’d talk to a campaign manager and they’d be like, ‘what do you think?’ and I’d be, ‘Look, I think you’ve got to do this, you’ve got do that.’ And they’d say, ‘Great! Can I get a selfie?’”

Mr. Carville has found plenty of other ways to make money. He worked as an adviser for campaigns overseas. And he made himself a brand, and a lucrative one, with television appearances, books, speaking engagements, a Coke commercial.

“James Carville figured out how to play James Carville on TV and make a living at it,” said Rahm Emanuel, who worked with Mr. Carville on the Bill Clinton campaign and is today the U.S. ambassador to Japan. “He’s as smart in politics as he is in marketing.”

The 1992 campaign was where he met his wife, Mary Matalin, the political director for George H.W. Bush, the Republican seeking a second term. The unlikely romance between two notoriously combative adversaries led not only to marriage but to a post-campaign, point-counter-point traveling road show that brought the two of them even more attention. (Their rich, if complicated, relationship is a major theme of Mr. Tyrnauer’s film. “I really have never liked having our marriage be the cause of our celebrity,” Ms. Matalin says to Mr. Carville in the film. “I don’t like it.”)

There is something poignant and intensely personal about Mr. Carville raising concerns about Mr. Biden’s capacity to do his job. He is just two years younger than Mr. Biden, and with every day, he said, he appreciates the kinds of challenges Mr. Biden faces. “The years become really long,” he said.

Mr. Carville walks stiffly to the elevator that takes him to the roof of the hotel. His balance is not what it once was. “You know, I’m getting to a point, I can see it coming, where I’ll need somebody to travel with me,” he said. “There are a lot of bags and escalators.”

Mr. Carville, an obsessive jogger when he was younger, is shown in the Tyrnauer documentary walking the halls of the Peninsula hotel as part of his morning exercise routine. “I think I’m running,” he said. “People think I walk.” He accepted the truth of it when he watched the documentary. “It was evident when I saw what I saw,” he said. “I’m walking.”

Mr. Carville watched the one and only debate between Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump from a hotel room in Aspen, Colo. He turned it off after the first few minutes of watching the president staring vacantly from the stage, ate two pot gummies and started listening to some Hank Williams. He said he realized at that moment that Mr. Biden would have to drop out.

By every account, Mr. Carville’s decision to act against Mr. Biden came after extensive consultation with a network of friends he has been talking to daily for 30 years. “I went into this with what you would call in the law malice and forethought,” he said.

And he was not alone — David Axelrod, another Democratic consultant, was warning the party publicly about the loss it was facing with Mr. Biden on the ticket. “Bill Maher, Jon Stewart, Ezra Klein,” Mr. Carville said, listing other people — all outside the Democratic Party leadership — who urged Mr. Biden to step aside.

“I could have been embarrassed,” Mr. Carville said. “He could have run and won. But it never occurred to me that I was wrong.”

At this stage in Mr. Carville’s life, there was not much to lose and it is hard to imagine him remaining quiet. “He can’t help it,” said Paul Begala, Mr. Carville’s partner on that 1992 campaign and one of his closest friends. “It is who he is. His income does not depend on being hired by politicians. Nor has it been for 30 years. He can say whatever he wants.”

Mr. Tyrnauer, who did not know Mr. Carville before he began this project, said he wanted to make a documentary that would be a tribute to politics, with Mr. Carville’s career standing as an inspiration to younger viewers who might be turned off by modern politics.

The film includes a scene from “The War Room” in which Mr. Carville fights back tears as he talks to a room full of young political operatives about the importance of their mission.

“It’s a hard time to be in politics,” Mr. Carville said, reflecting on his work. “Everyone who is part of it feels beleaguered. The surest line you can use to get applause is, ‘I hate politics.’”

“Actually,” he said. “I don’t.”

The post James Carville on Aging, Edibles and His Anxieties About Harris appeared first on New York Times.